I touched on this story in June 2020 in my piece about the red herring of Roger constable of Chester and the crusade.

I am not able to say who wrote the text below, only that I have it from the work known as Gesta Henrici Secundi and that it is an old text with a complicated history. I do not know exactly when it was written, or whether the writer was drawing on first-hand knowledge.

The story has been referred to in various published works in various abridged forms. I have decided to put it here in the longest version that I have found, in latin.

I found it easy to get the gist of it, but very hard to translate word for word, so what follows - the English version - is just the gist!

...............

Eodem anno Rogerus constabularius Cestriae, filius Johannis, cui Willelmus Eliensis episcopus, dum esset totius Angliae justitiarius, tradiderat castellum de Notingeham et castellum de Tikehil, in fidelitate regis custodienda, ........

The same year [clearly meaning 1191] Roger constable of Chester, son of John, to whom William bishop of Ely, when he was Justiciar of all England, entrusted the castles of Nottingham and Tickhill to hold faithfully for the king, ......

At least one published translation of this states that the castles were entrusted to Roger, and whether this is right depends on how you read the first sentence. I have left it ambiguous also in English. But I think it means the castles were entrusted to John Constable of Chester, otherwise there would be no point in mentioning him. William Longchamp became Chancellor and bishop of Ely in September 1189, shortly after Richard I came to the throne. The castles must have been placed in John's hands very early on because he, if the accounts are correct, proceeded to the Middle East where he died, apparently in October 1190. Some old editors called him "de Lacy," which is incorrect, and may be a reflection of some other muddle. Richard I left England in mid December 1189 and did not return till 1194.

...... doluit vehementer quod servientes sui quibus ille praenominata castella tradiderat in custodia, scilicet Robertus de Crocstune, quem ipse fecerat constabularium de Notingeham, et Eudo de Daiville, quem fecerat constabularium. de Tikehil, ........

...... was greatly pained that his officers to whom he ["ille" - presumably meaning John] had committed custody of the said castles, namely Robert of Croxton, who he had made constable of Nottingham, and Eudes de Daiville, who he had made constable of Tickhill, .....

See previous note. I think that Roger was upset because these men would have given undertakings to his father, and I think that such an undertaking given to a person known to be about to depart on the Crusade was particularly strong.

...... ita inconsulte et sine insulto tradidissent praenominata castella Johanni comiti Meretonii.

.......without consulting him and without being attacked had delivered the said castles to John count of Mortain.

Et apposuit ut comprehenderet illos, sed illi inde praemuniti custodiebant se, male sibi conscii, et de venia desperantes juri stare noluerunt.

And he tried to arrest them but they were forewarned...... got away ..... they refused to stand trial.

Et ideo nomen proditoris in aeternum non deficiet illis.

And so the traitors got away from him for ever.

|

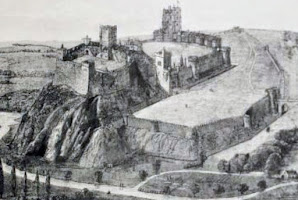

| Nottingham castle as it might have been |

And the said Roger constable of Chester arrested Alan of Leake, with whom Robert of Croxton was associated in the custody of Nottingham castle.

|

| and as it is |

I suspect Alan is named from Leake (East or West), south of Nottingham, rather than Leek (Staffordshire).

Apprehendit et Petrum de Bouencurt, Normannigenam [sic], quem ipse associaverat Eudoni de Daivilla in custodia castelli de Tikehil;

And he arrested Peter de Bovencurt, a Norman (?), with whom Eudes de Daiville was associated in the custody of Tickhill castle.

et utrumque illorum suspendit in patibulo,

and hung them both on the gibbet,

licet praedictus Petrus de Bouencurt, statim post traditionem castelli de Tikehil, venisset Lundonias, in conspectu Johannis comitis Meretonii, ......

However the said Peter de Bovencurt, immediately after the handover of Tickhill castle, had gone to London, to see John count of Mortain, .......

There is a shorter and in some respects different translation of this story in John T. Appleby's "England without Richard," (1965) at page 69.

et in curia regis, coram cancellario, voluisset innocentiam suam purgare: constanter affirmans quod castellum de Tikeliil traditum fuit comiti Johanni contra voluntatem et prohibitionem suam;

and in the king's court, before the chancellor, had said he wanted to prove his innocence; steadfastly declaring that Tickhill castle was handed over to count John against his wish and against his order[s];

et quod si ipse habuisset socios qui essent unanimes ad defendendum illud contra comitem Meretonii, sicut ipse voluit, non esset traditum in manu illius.

and that if he had had associates who were agreed about defending [it] against the count of Mortain, as he had wanted, it would not have been delivered it into his hands.

Cancellarius vero noluit purgationem inde ab eo recipere; sed remisit eum ad curiam constabularii Cestriae, dicens illi,

But indeed the Chancellor refused to purge [clear, acquit] him but sent him to the court of the constable of Chester, saying to him

" Vade ad dominum tuum constabularium, et in curia ejus purga innocentiam tuam a crimine quod ipse tibi imponit.”

"Go to your lord the constable, and in his court prove your innocence of the crime that he charges you with / places on you."

Qui cum illuc venisset cum litteris comitis Meretonii supplicantibus, obtulit se modis omnibus purgare innocentiam suam a crimine quod dominus suus ei imponebat; scilicet quod nec praecepit nec voluit nec in aliquo consensit quod castellum de Tikeliil traderetur comiti Johanni ; immo in quantum potuit prohibuit ne traderutur illi.

[And he] thereupon came with letters from the count of Mortain, and offered by all means to clear himself as innocent of the crime his lord laid on him; namely that he did not order or wish or in any way or consent that Tickhill castle be handed over to count John; indeed that to the extent of his power, he forbad it.

At praedictus constabularius Cestriae noluit inde recipere purgationem ab illo, sed sine judicio ilium suspendit in patibulo cum catena ferrea.

And the said constable of Chester would not accept this as proof of his innocence, but without trial, hung him on a gibbet with iron chains.

In Appleby's translation both Alan and Peter are hung on the iron chains, and the birds feast on both corpses. But the whole of this second part of the story seems to me to relate to Peter.

Deinde post triduum suspendit quendam armigerum suum, pro eo quod ipse abigebat aves a corpore illius pendentis in patibulo, quae carnes ejus unguibus et rostris dilacerabant.

And thereupon after three days he hung a certain squire of his, as he was driving birds away from his body hanging on the gibbet, which were picking at his flesh with their claws and beaks.

Johannes autem comes Moretonii, in vindictam praedictorum suspensorum dissaisiavit praedictum constabularium Cestriae de omni tenemento quod de illo tenuit, et terras suas devastavit.

John count of Mortain, in retribution for the said hanging, disseised the said constable of Chester of all property that he held of him, and laid waste to his lands.

- Note. In this text the verb "trado" is used several times. It can mean hand over, deliver, entrust, consign, surrender treacherously, and so on. So the gist seems to me that the castles were entrusted to John constable of Chester to hold for the King. The logic of this was clear enough - Nottingham itself was a royal castle, but the constable of Chester had claims on Tickhill, and their own castle nearby at Donington. He had numerous estates within close reach of Nottingham and Tickhill from which he could draw men and supplies. Shortly after taking on this charge however John appears to have departed to the Middle East, where he died, possibly in late 1190. News of this would have come back to England as count John's mainly north of England rebellion was gathering momentum. I have taken "doluit vehementer" to mean that Roger was strongly affected - by the breach of promises to his father. A few years later, of course, and Roger was reconciled with and working for the former Count John, who became king in 1199.

Please refer to the Preface by Bishop Stubbs to the (1867) two volume Rolls Series edition of the Gesta Regis Henrici Secundi, and to later opinions. The text itself has been taken from Vol. 2 of that edition, pages 232-234. The incident in question is chronologically one of the last (latest) stories to be recounted. See page xxviii of the Preface in Vol. 1.

Despite its title the edition of course includes many pages of events in the reign of Richard I including much information about the Third Crusade. Quite suddenly on page 207 of Vol. 2 in the printed edition, it "flips" to events in England in 1191, specifically at Lincoln, Tickhill, and Nottingham. I have seen nothing suggesting that there was any fighting or resistance at either Nottingham or Tickhill. The implication is that the chancellor was focussed on Lincoln at the time. These events were early in the year, as a treaty reached at Winchester in ??March 1191 mentions Nottingham and Tickhill as already being in count John's hands, and they were to be handed over to new castellans on behalf of the king. I suspect that that "hand back" never happened - Nottingham for example was in the hands of rebels until 1194 when King Richard returned.

EMB 17 February 2021

No comments:

Post a Comment